The subtitle “The Pennsylvania Miners Who Seized an Industry” might lead you to believe that The Bootleg Coal Rebellion it is all about men. That’s not true. When I say “bootleg miners” I am including women, because they did work the bootleg coal holes, above ground and below. And that’s not all they did.

Diana Baldwin is famed as the first female coal miner, hired onto a Kentucky bituminous mine in 1973. It is probably only fair to call her the first legal female coal miner in the US, but only with those caveats. When industrial coal mining began in Britain, for instance, much of it was women’s work (even after they were banned from underground work in 1842). Women also worked underground during the Great Depression, but they so in illegal mines.

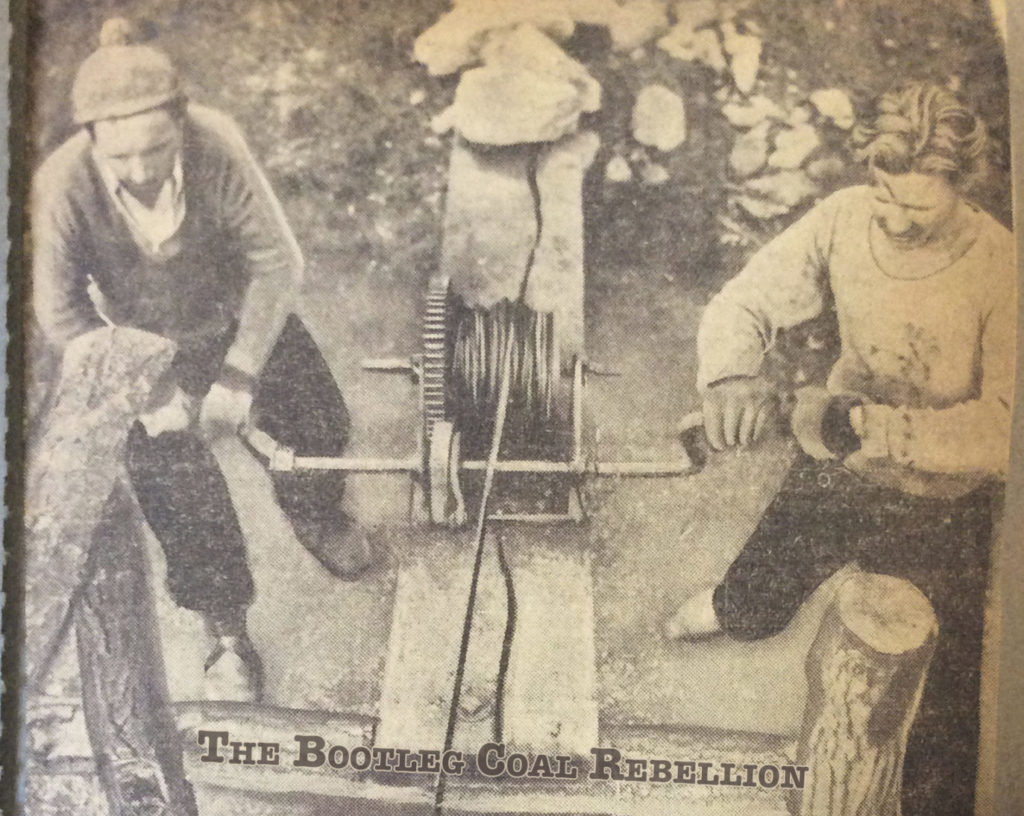

When the collieries of the lower Anthracite Coal Region closed in the 1930’s, miners sank small “coal holes” on company lands. They ran these primitive mines cooperatively between a few out-of-work “partners,” with each partner’s family working alongside them 6 days a week. Women and children typically contributed to the above-ground work: cranking, breaking, sorting, screening, hauling, and selling of coal. Though less common, many women also worked underground. One of them was Mary W:

“I know a little bit about bootleg coal. In those days, that was the only thing… to survive. Even my mother and my sisters and I used to go into the drift. We used to scoop the coal after my father would fire. We’d scoop it on a wheelbarrow and wheel it out and… scoop it on a truck and my brothers would haul it home… We used to scoop it on different screens to size it… stove coal, nut coal, pea coal, buckwheat. I know a little bit about coal!”[1]Quoted in Michael Kozura, “We Stood Our Ground,” in We Are All Leaders: The Alternative Unionism of the Early 1930s, ed. Staughton Lynd (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 199–237.

Rarer still, some women were partners in their own right. Some lost their husbands and took up his place as a partner until other arrangements could be worked out. Other women were heads of “non-traditional” households (which were, in fact, very traditional too) and were full partners. They did the work for the same reason as male bootleggers: because they had to. A bootleg union leader even remembered a woman near Tower City who run her mine up until at least 1949. She was a full, dues-paying member of the Independent Miners, Breakmen, and Truckers Association (bootleg union). It’s unclear if her mine was on illegal land.

So far this has equated mining with underground work. But it’s not right to say women got involved in mining when they went down into the earth. Women of the anthracite did much of the prep work for underground miners. That includes the home-work that kept men alive and well, of course. But it also meant handling explosives. Men were required to provide their own explosives and it was typically women working at home who packed the “squibs.” That meant gently tamping black powder down into pieces of straw and twisting the ends shut. Miners needed a pouch-full each workday. So they certainly risked their lives for coal mining, if not underground while doing it.

More famously, women were also the traditional backbone of strikes. When weary (and often drunken) men hung their heads in defeat, women rallied them back to the picket lines. As the traditional managers of money and necessities, they would not accept the low wages men were paid nor the terrible conditions that could widow them. Women and children’s picket lines were frequent in both anthracite and bituminous strikes throughout US history. The much loved Mother Jones traveled the country for the United Mine Workers (and later, for the Socialist Party) brow-beating men and rallying women around the turn of the 20th century. Many bootleg families would have known her—her memoirs are full of dramatic stories from the lower coal region.

The coal region had its own home-grown Mother Jones’s as well. Most of their names have been lost to history, but two we know are “Big Mary” Septek and Mrs. Martin McCrone. The following is a quote from The Bootleg Coal Rebellion. Immediately following the 1897 Lattimer Massacre near Hazleton:

Big Mary believed Lattimer miners to be too docile. She formed a women’s group to enforce the strike. Joined by one hundred fifty to three hundred women on any given day, they marched on collieries as far as ten miles away, sometimes visiting four in one day. They were armed with clubs, rocks, scrap iron, pots and pans, wooden spoons. Another women’s group formed in nearby Honeybrook, led by Mrs. McCrone, who had no shoes and often smoked a pipe while marching. The women’s groups gave strike breakers warning to leave, after which they attacked the collieries and bloodied the strike-breakers they could get their hands on. Sometimes they forced their way into company offices to pull the shift whistle. At night, men and women marched through their town streets together, banging pots and pans, making everyone very aware that no one should go back to work.[2]This excerpt from The Bootleg Coal Rebellion is copyright 2021 by Mitch Troutman. Do not use without permission.

This same spirit was alive and well in bootlegging thirty years later. When police or stripping shovels arrived to shut down the bootleggers, bells and alarms were sounded and a town’s women and children rushed to the scene. They made picket lines, stood in the path of machinery, and even climbed into the buckets of the massive power shovels. You can’t separate any of this audacity, this work, or this risk from the business of mining bootleg coal.

To learn more about Big Mary, Mrs. McCrone, and the women who dug coal, preorder the Bootleg Coal Rebellion! Use the code “BOOTLEG” for 20% off the cover price.

References

| ↑1 | Quoted in Michael Kozura, “We Stood Our Ground,” in We Are All Leaders: The Alternative Unionism of the Early 1930s, ed. Staughton Lynd (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996), 199–237. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This excerpt from The Bootleg Coal Rebellion is copyright 2021 by Mitch Troutman. Do not use without permission. |